Freemasonry In Brother Mark Twain's Story "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy"

Bruce G. Chabot, 32

College Station, Texas

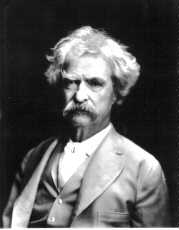

Brother Samuel L. Clemens (pictured, also known as Mark Twain) stopped writing "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy" in 1897, leaving it unfinished, and it remained unpublished until it appeared in the Bancroft Library/University of California-Berkeley's Mark Twain Papers (1969) and in Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer Among the Indians And Other Unfinished Stories (1989). "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy" is "a parody of popular detective fiction that stops just pages shy of completion" (Armon, p. xiv). Twain also wrote several other detective spoofs, including Tom Sawyer: Detective and A Double Barrelled Detective Story. The detective stories Twain was parodying include those of Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle. Twain had the works of both authors in his library, as well as those of Rudyard Kipling (Gribben, pp. 201, 380, 551), who, like Conan Doyle, was a Mason and liberally scattered allusions to Freemasonry throughout his writings (especially "The Man Who Would Be King" in 1885).

Like his contemporaries Bros. Rudyard Kipling and Conan Doyle, Mark Twain was also a Freemason, and, like them, Twain occasionally placed allusions to Freemasonry in his works, particularly in "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy."

Fraternal societies proliferated during the nineteenth century in America. Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Twain's real name) was a member of St. Louis's Polar Star Masonic Lodge No. 79, many of whose members were river pilots (Jones, p. 364). Clemens petitioned for admission in 1860 and was initiated into all three Blue Lodge Degrees of Freemasonry in the following year. For almost ten years, he participated in the Masonic Fraternity whenever his circumstances allowed, and he occasionally visited other Masonic Lodges and socialized with fellow Freemasons. Ultimately, he let his regular attendance lapse. However, he seems to have sustained a high regard for the Fraternity throughout his life.

While on a trip to the Middle East in 1867, for instance, Twain "visited the forest of the Lebanese cedars from which King Solomon is thought to have taken timber for his temple-a symbolic site for any Mason," (LeMaster, p. 304). He took a sample of the wood home with him, later having it made into a ceremonial gavel which he gave to the officers of his Lodge.

Alexander Jones argues that Twain was so impressed by Masonic attitudes toward religion that they influenced his own view of God, and that this influence is reflected in The Innocents Abroad. Examples include Twain's referring to God as the "Great Architect of the Universe" and his repeated ruminations on King Solomon and the cedars of Lebanon as well as his thoughtful descriptions of mosques where he describes marble "that once adorned the inner Temple" (Jones, pp. 365-73).

Clearly, Masonic history and symbolism underlie much of "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy." The beginning of the story is largely taken up with Tom, Huck, and Jim discussing ways to relieve the boredom of the summer. Tom suggests they start a civil war or, better yet, a revolution, which he defines as an uprising "full of patriotic devotion" (Twain, "Conspiracy," p. 138). Freemasons have traditionally frowned upon any kind of subversion of legitimate government, even prohibiting it in their rules and regulations. The Masonic Constitutions of 1723 declare that "A Mason is a peaceable subject to the Civil Powers, wherever he resides or works, and is never to be concerned in plots and conspiracies against the peace and welfare of the nation" (Coil, p. 142).

However, historically many famous Masons agreed with the sentiments of the Declaration of Independence, paraphrased by Tom Sawyer in this story, to the effect that when a government becomes unjustly burdensome, it may have to be cast aside in favor of a new one.

Tom's admiration for patriotism and revolution suggests a subtextual association with a historic source of Masonic pride, namely those Masons who have been involved in patriotic causes and revolutions, especially the several famous figures in the American Revolution who were Masons, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Paul Revere. Freemasons in Texas often point out that many of the leaders of the War for Texas Independence were members of their organization, including Jim Bowie, Sam Houston, and Davy Crockett.

Tom Sawyer, of course, talks about patriotism and revolution with youthful enthusiasm, but with little understanding. In his immature mind, the most important thing is the concept of conspiracy. The subject of conspiracy is a serious one for Masons. Since the eighteenth century, the Masonic Fraternity has been attacked by various religious and political groups and has been accused of everything from plotting to overthrow the government of the Catholic Church and planning political assassinations to controlling international economies and worshipping the devil (Normand, pp. 8-9).

Twain's humorous use of Tom's infatuation with fantastic distortions of the idea of conspiracy suggests a comparison with these outlandish accusations. Such a comparison implies that the charges against Freemasonry are equivalent to Tom's ridiculous machinations blown out of proportion by the frightened, gullible townsfolk.

Students of Freemasonry will find Tom's oaths, and the penalties for breaking them, significant because they bring up a theme often used in anti-Masonic polemic. To wit, some religious critics of Freemasonry accuse Masons of "what they term `bloody oaths'" (Masonic, p. 3). The Masons, however, view these oaths and penalties as not literal but symbolic in that they refer to "the shame a good man should feel at the thought he had broken a promise." Also, they remind Masons of punishments actually given in medieval Europe to people who were convicted of "fighting for civil liberty and religious freedom." Masons consider such people their intellectual forbearers (Masonic, p. 3).

The context of the oaths that Tom makes up in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn makes it clear that they, too, are more metaphorical than literal. Tom explains that he got the ideas from books about pirates and robbers, and all the boys agree that the oaths are high-toned and beautiful. Then, the boys spend quite a while planning out how they will rob, murder and ransom people, none of which they seriously intend to do. Although such plans would take on an entirely different meaning in connection with juvenile crime in late twentieth-century urban America, for Huck and Tom the whole affair is obviously boyish nonsense. The effect of Twain's rendering the subject in this comical fashion is to suggest that the corresponding accusations against Masons are similarly absurd.

When Tom and Huck go out at night among the men patrolling the frenzied town, a sentry orders them to give the countersign in order to be recognized as "Friends." Such a means of recognition mirrors the custom among Freemasons and other fraternities of using passwords and handshakes known only to those who belong in order to test one another or establish their identity as members.

The most explicit Masonic allusions in the story appear in Chapter Four, which deals with Mr. Baxter, the printer. Baxter is a well-respected citizen and a friend of all. Huck enumerates Baxter's civic honors and fraternal positions:

"[H]e was Inside Sentinel of the Masons, and Outside Sentinel of the Odd Fellows, and a kind a head bung-starter or something of the Foes of the Flowing Bowl, and something or other to the Daughters of Rebecca, and something like it to the King's Daughters, and Royal Grand Warden to the Knights of Morality, and Sublime Grand Marshal of the Good Templars, and there warn't no fancy apron agoing but he had a sample, and no turnout but he was in the procession, with his banner or his sword, or toting a bible on a tray, and looking awful serious and responsible, and yet not getting a cent. A good man, he was, they don't make no better." (Twain, "Conspiracy," pp. 159-60).

Huck's long list of fraternal organizations fixes Baxter as a very active Masonic Lodge member and an upstanding member of the community. Baxter is also praised by Huck for "being a pillow of the church and taking up the collection, Sundays, and doing it wide open and square" (Twain, "Conspiracy," p. 159; sic). Twain's use of the word "square" in reference to Baxter provides another possible Masonic allusion because the builder's square is a vital tool in construction and is thus an important symbol for Masons.

The final Masonic allusion in "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy" appears on the flyers that Tom prints to advertise his conspiracy. Through the flyers, Tom creates an imaginary abolitionist group called the "Sons of Freedom" and warns that they will run slaves out of town. At the top of the page, as a logo for his group, Tom draws an eye, which he says "stood for vigilance and was emblumatic" (Twain, "Conspiracy," p. 169; sic). Such an eye is prominent in Masonic symbology, where it represents the all-seeing eye of God watching over mankind. This Masonic symbol, which coincidentally also appears on the American one dollar bill, is part of many types of Masonic emblems, such as the Square and Compasses logo, which may have at its center an eye, a sunburst, or a capital letter G, all of which stand for God and form a reminder of the centrality of God in the life of every Freemason.

In summary, Mark Twain uses Masonic imagery throughout many of his works,

especially in "Tom Sawyer's Conspiracy." While such Masonic allusions may

be more obvious to Masons reading Twain's work, anyone aware of the fact

that Twain himself was a Mason should be able to recognize them. Clearly,

the time Twain spent participating in and learning about Freemasonry made

a lasting impression on him, and the light he gained Masonically shone

through in his life and in his works.